01 Mar Champ Ferguson

Hell Along the Border

by Ron Soodalter

“Murders for old grudges, and murders for pelf, proceed under any cloak that will best cover for the occasion.”

— Abraham Lincoln

After the October 1864 Battle of Saltville in Virginia, Union Lt. Elza C. Smith of the 13th Kentucky Cavalry lay wounded in the Emory and Henry College Hospital along with several of his white and African-American troopers. Suddenly, Rebel guerrilla Champ Ferguson burst into the ward at the head of his band. He strode across the room, and when he came to Smith’s cot, he raised his rifle and snarled, “Do you see this?” He placed the muzzle a foot from Smith’s forehead as the injured man lay helpless, pleading for his life. Ferguson drew back the hammer, and … CLICK! The weapon misfired. He cocked his rifle and pulled the trigger twice more, with the same result. Finally, mercifully, on the fourth attempt the gun discharged, and Smith lay dead on his cot, a bullet through his head.

An old adage maintains that history is written by the victors—and to a large extent, this is true. Yet, at the end of the Civil War, our nation’s bloodiest struggle, only two men were tried and executed for war crimes. Both had served the Confederacy. One was Henry Wirz, commandant of the notorious prisoner-of-war camp at Andersonville, Ga.; the other was Rebel partisan ranger and guerrilla fighter Champ Ferguson. There is room for extenuation in the case of Wirz, an ineffectual martinet clearly out of his depth; the same cannot be said for Ferguson. While some romantics have doggedly held to the image of Champ Ferguson as a much-wronged Southern patriot and freedom fighter, he was in fact a vicious killer who took life with neither conscience nor compunction.

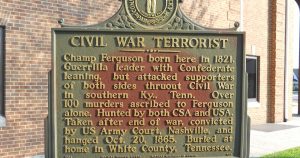

In the Cumberland Mountains community of Albany, Ky., the seat of Clinton County, there stands a plaque that reads: “Civil War Terrorist Champ Ferguson born here in 1821. Guerrilla leader with Confederate leaning, but attacked supporters of both sides thruout Civil War in southern Ky., Tenn. Over 100 murders ascribed to Ferguson alone. Hunted by both CSA and USA ….”

Ferguson was very much a product of his time and place. A relatively successful south-central Kentucky farmer, he was born into a Southern mountain border culture that embraced the blood feud and justified violence, often unto death, as a means of resolving personal differences. Kentucky-born Abraham Lincoln well understood the mentality when he wrote, “Each man feels an impulse to kill his neighbor lest he be first killed by him.” To Champ Ferguson, the world was a simple place, consisting of friends and enemies. The former were to be embraced; the latter, eliminated. In 1858, he killed his first man, stabbing a local constable over a financial dispute. According to his own account, when he joined the war three years later, it was less because of his commitment to the Southern cause than as a means of escaping prosecution. By this time Ferguson was 39, but despite the late start, he would soon add dozens of killings to his tally.

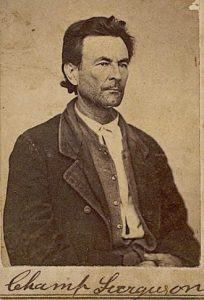

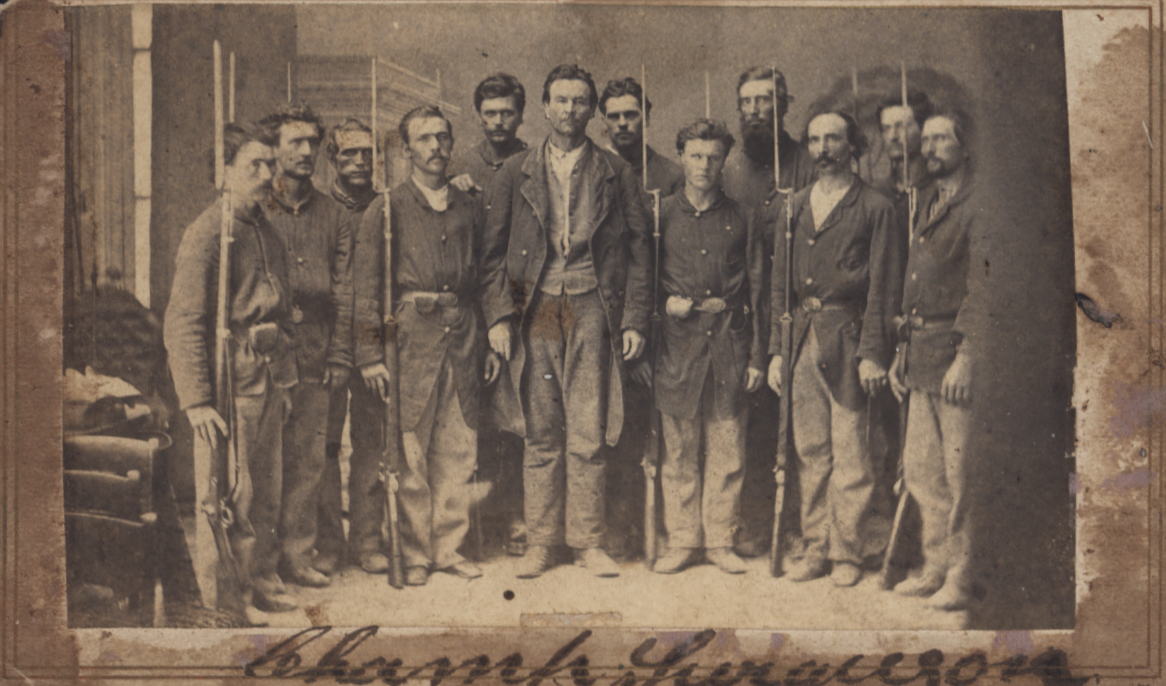

At 6 feet in height and weighing some 180 pounds, Ferguson was an imposing figure with a reputation around his hometown as a drinker, gambler and bully. His powerful physical appearance, combined with what one historian referred to as his “primordial” nature, struck terror in the hearts of his enemies. As with many who lived in the conflicted border states, his war had less to do with fighting for Southern independence than settling scores with neighbors—and in some cases, with blood kin—who happened to be on the wrong side. He himself later described his guerrilla band’s theater of operations: “We were having sort of a miscellaneous war, up there, through Fentress county, Tennessee, and Clinton county, Kentucky, and all through that region. … Each of us had from 20 to 30 proscribed enemies, and it was regarded as legitimate to kill them at any time, at any place, under any circumstances.”

He did exactly that. His first victim was a neighbor, William Frogg. When he rode up to the Frogg cabin, Mrs. Frogg suspected no ill will; she had known Champ since childhood, and she offered him a seat and an apple. He refused both and sought out her husband, who lay ill in his bed. Champ inquired as to Frogg’s health, and his neighbor responded, “I am very sick. I had the measles and have had a relapse.”

Champ accused Frogg of having contracted his illness while visiting the Yankee recruitment center at nearby Camp Dick Robinson, which Frogg vehemently denied. Ferguson simply drew his pistol and shot Frogg twice in front of his wife and child, killing him on the spot. He then ransacked the cabin, looking for weapons. At his trial four years later, Ferguson would voice what would become his constant refrain: “I considered myself justified in killing him.”

One month later, Champ saddled and stole the horse of another local citizen while loudly cursing the man for a “God-damned Lincolnite” and threatening to kill him. That same day, he rode the stolen horse to the farm of Reuben Wood, a man who had been a lifelong friend until the war put them on opposite sides. As Wood finished feeding his livestock and was entering his house, Champ rode up with two Confederates and said, “I suppose you have been to Camp Robinson.” It appears that to Ferguson, simply visiting the Yankee recruitment center earned a man a death sentence. Wood acknowledged that he had, to which—according to the later testimony of Wood’s daughter—Ferguson responded with a long, “violent and bitter” diatribe, ending with, “Don’t you beg and don’t you dodge!” Wood’s wife and daughter pleaded for his life, while the old man himself reminded his visitor, “Why, Champ, I have nursed you. Has there ever been any misunderstanding between us?”

Ferguson coldly replied, “No, Reuben, you have always treated me like a gentleman, but you have been to Camp Robinson, and I intend to kill you.”

And he did.

Clinton County, Ferguson’s home and birthplace, was overwhelmingly Unionist in its sympathies, as was nearly all of Champ’s own family, and the killings of Frogg and Wood, as well as the blatant theft of livestock, had roused the countryside against him. After his father’s death, Reuben Wood’s son gathered a small band of armed men for the express purpose of killing Champ Ferguson. He missed his chance, and Champ quickly moved across the border into secessionist Tennessee with his band of brigands, settling in White County, along the Calfkiller River. By this time, Champ’s brother, Jim, had joined the Union’s 1st Kentucky Cavalry as a scout, and the brothers had sworn to kill each other on sight—which no doubt would have happened had Jim not been ambushed in December 1861.

The Tennessee-Kentucky border was hotly contested by both Union and Confederate forces throughout the war, and from time to time, Champ found himself serving with regular Rebel units, most notably as a scout for the calvalry of the legendary John Hunt Morgan. However, he preferred to function on his own, without the bothersome rules of military conduct to impede him. His former home, Clinton County, became the scene of vicious guerrilla fighting. Ferguson’s opposite number, local hardcore Union partisan and guerrilla leader David “Tinker Dave” Beatty, swore to kill Champ, and each gave as good as he got, with atrocities committed on both sides.

By the winter of 1862, conditions had gotten so out of hand along the Kentucky-Tennessee border that members of partisan bands from both sides met in Monroe, Tenn., to discuss a cessation of hostilities. It was agreed by those attending, including Tinker Dave, that they would cease the wanton killing and looting, lay down their weapons, and go home. However, with a regional peace within their grasp, a handful of Rebel guerrillas—including Champ Ferguson—immediately broke the terms of the agreement, ensuring the mayhem would continue.

Throughout the four years of war, Ferguson killed regular soldiers, members of the Home Guard, and simple farmers. He slew helpless prisoners and the children of his enemies. At one point, he berated one of his men for sparing the lives of fleeing boys, screaming, “God-damn them … You ought to have shot them.” He murdered five men in one day alone, the last a local youth of 16. Although he sometimes used his pistol or rifle, he reportedly preferred to do his killing “up close and personal” with a Bowie knife.

Champ apparently was ever alert to the possibility of personal gain. Clergyman Isaac T. Reneau wrote in a letter to Tennessee governor and future president Andrew Johnson, “Ferguson has been engaged in horse stealing on a large scale ever since the great rebellion began, and, it is supposed, has stolen thousands of dollars’ worth of property.”

The most deliberate, cold-blooded murders perpetrated by Champ Ferguson occurred after the Battle of Saltville. Both before and after the killing of Lt. Elza Smith described above, Ferguson and his men rampaged through the hospital and the grounds, slaying injured black troopers where they found them as well as the white soldiers and officers with whom they served. Espying one wounded young white trooper crawling along the ground, Ferguson demanded why he had “come down there to fight with the damned niggers.” Ferguson drew his pistol and asked the hapless soldier, “Where will you have it, in the back or in the face?” The terrified youth was incoherent with pain and fear, so Ferguson peremptorily chose for him.

So outraged was the Confederate high command at Ferguson’s conduct at Saltville that they ordered his arrest. He was incarcerated on Feb. 8, 1865, but by this time, Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia was on the run, and the war was all but lost for the South. Brig. Gen. John Echols ordered Champ released within days of Lee’s surrender, and soon thereafter—with the Confederacy crumbling around him—Ferguson was back in the Cumberland, weapons in hand, resuming his bloody personal war. He slew his last two men on May 1, and within days, Union Maj. Gen. George Thomas ordered that Ferguson be declared an outlaw and his surrender refused. Champ’s former comrades, presented with the possibility of parole, urged him to surrender rather than bring the wrath of the victorious Northern army down on them all. By month’s end, Ferguson was arrested at his home and charged with murdering 53 men.

At his trial, the prosecution paraded 43 witnesses before the jury, each with a personal story of how the defendant had murdered a friend or loved one. One of the most damning witnesses was none other than Tinker Dave Beatty, whose offenses on behalf of the Union were arguably as heinous as those of his long-term adversary, but who had the good fortune to have come out on the winning side. Ferguson displayed no remorse whatsoever and, when allowed to speak, either denied or attempted to justify his killings. Former Confederate general and cavalry commander Joseph Wheeler was one of the few to speak on Ferguson’s behalf, but the jury was unimpressed; it convicted Champ on all counts and sentenced him to hang. In his final statement, he said, “I die a Rebel out and out, and my last request is that my body be removed to White County, Tennessee, and buried in good Rebel soil.”

Champ Ferguson was executed on the morning of Oct. 20, 1865. Just before he was dropped through the trap, his voice rang out over the crowd of silent observers: “Good Lord have mercy on my soul!” The short drop failed to break his neck, but rendered him unconscious. He lived for some 17 minutes before the attending physician pronounced him dead. His wife and daughter took him home to White County and buried him in the local churchyard, according to his last wish.

Americans love their outlaws. By combining the Robin Hood image with the myth of the Lost Cause, the South minted such would-be folk heroes as Jesse James, Cole Younger and Champ Ferguson, assigning them in death a nobility they lacked in life. Their apologists created or subscribed to fables describing how they were “driven to it” by a cruel and brutal foe. Such stories grew up around Champ Ferguson even while he lived. One tells how his wife and daughter were “outraged” by Union soldiers—some versions have them killed—driving Champ to join the war to seek revenge. Another tale describes how Champ’s 3-year-old son was shot dead by a Yankee soldier for waving a small Rebel flag—an impossibility considering his only son had died of illness in 1847. According to some contemporary sources, Champ himself occasionally fell back on these falsehoods to justify his actions, although, shortly before his death, he acknowledged that they were complete fabrications. In reality, Champ Ferguson was nothing more than a mass murderer who displayed an unbridled willingness to take human life, without remorse and for his own personal reasons. In the end, he richly deserved to perish at the end of a rope.

Article published in Kentucky Monthly, October 12, 2012